Imagine looking at an old photograph of yourself and wondering if the person staring back is truly the same person you are today. This question of identity lies at the heart of the Ship of Theseus, a classic philosophical puzzle that challenges our understanding of persistence and change. As the Athenians replaced each decaying plank of the legendary vessel, they sparked a debate that has fascinated thinkers for millennia. Does an object remain the same if all its parts are replaced? It forces you to confront whether your essence is tied to your physical material or something more abstract.

Thomas Hobbes deepened the paradox with a twist. He asked what happens if someone gathered all those discarded, rotting planks and reassembled them into a second, identical vessel alongside the restored one. Now you face two ships claiming the same identity, leaving you to decide which one holds the true title. This enduring riddle isn’t just about wooden boats; it is a profound inquiry into the very nature of existence.

Key Takeaways

- The Ship of Theseus paradox fundamentally questions whether an object’s identity is defined by its physical material or its continuous history and form.

- Thomas Hobbes expanded the inquiry by introducing a second ship reassembled from discarded parts, forcing a direct choice between material authenticity and structural continuity.

- This ancient riddle mirrors human biology, suggesting that personal identity relies on the continuity of consciousness rather than the persistence of specific atoms.

- Distinguishing between numerical and qualitative identity helps resolve the paradox by revealing that identity is often a constructed concept rather than a static physical fact.

Plutarch’s Puzzle of the Rotting Planks

Picture yourself walking through ancient Athens and finding a relic that sparks a debate lasting for millennia. According to the Greek historian Plutarch, the Athenians preserved the thirty-oared galley of Theseus to honor his legendary return from Crete. As the years passed, the wood inevitably began to rot, forcing caretakers to remove old planks and install fresh timber in their place. This process continued slowly until every single original piece of the vessel had been replaced by new material. You are then left with a fascinating question regarding whether this restored craft is still the same object that sailed the seas.

Plutarch noted that this ship became a standing example among philosophers investigating the nature of growth and identity. Some argue that the ship remains identical because its form and function occupy a continuous history. Skeptics insist that once the physical substance changes, the original identity vanishes completely. This puzzle forces you to consider what truly defines an object over time, be it the material it is made of or the structure it maintains. It challenges your intuition about continuity in a way that feels surprisingly relevant to your own changing self.

Later thinkers like Thomas Hobbes added a twist to the original scenario. Suppose a scavenger collected all the discarded rotten planks and carefully reassembled them into a second ship. You now have two distinct vessels, yet both have a legitimate claim to being the original Ship of Theseus. One possesses the continuity of form, while the other holds the original physical matter. This extension of the paradox leaves you wondering not just if identity persists, but if it can exist in two places at once.

Thomas Hobbes and the Rival Ship Scenario

Even if you solve the puzzle of the renovated ship, the 17th-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes introduces a complication that might change your mind. He asks you to imagine a scavenger who diligently collects every single decayed plank as it is discarded from the original vessel. Over time, this scavenger reassembles these old, rotting pieces to build a second ship that is structurally identical to the original. Now you are faced with two distinct vessels claiming the title of the Ship of Theseus. One is made of new, sturdy timber, while the other consists entirely of the original material.

This scenario forces you to choose between two competing definitions of identity that usually coexist without issue. If you prioritize material composition, then the scavenger’s reconstruction must be the true ship because it holds the original parts. However, if you argue that identity relies on the history and functional life of an object, then the renovated ship in the harbor remains the authentic one. Hobbes effectively breaks the link between the substance of an object and its form. You are left wondering if an object is defined by its atoms or by the path it travels through time.

Defining Identity and Persistence Over Time

To understand the Ship of Theseus, you must distinguish between two types of sameness. Philosophers distinguish between numerical identity, meaning one specific object, and qualitative identity, which refers to things sharing identical properties. If you own two identical mass-produced cars, they are qualitatively the same but numerically distinct entities. When the Athenians replaced every plank in Theseus’s ship, the resulting vessel certainly maintained its qualitative identity by looking exactly like the original. The real puzzle lies in whether it retained its numerical identity or became a completely new object through the process of repair.

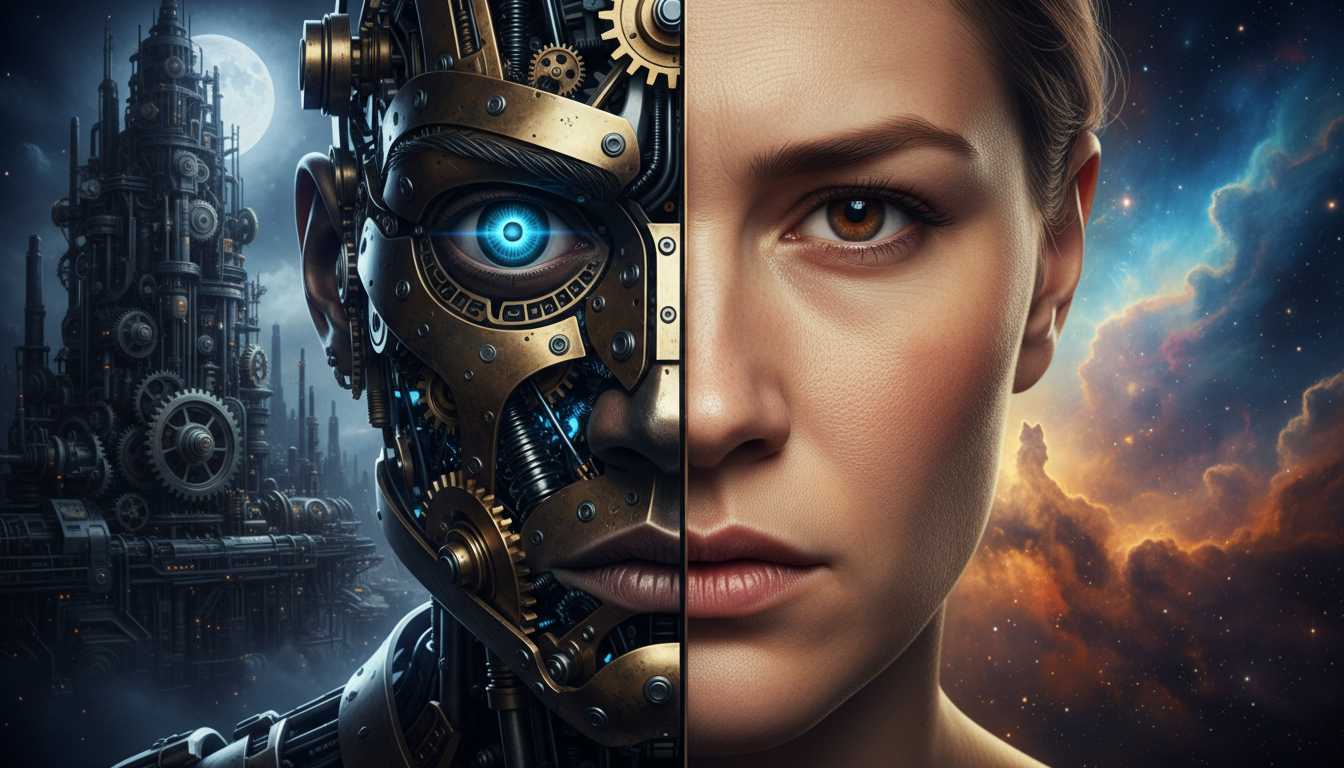

This ancient paradox becomes personal when you apply it to your own physical existence. Just like the gradually replaced timber of the ship, your body is in a constant state of biological flux. Your cells die and regenerate at such a rapid pace that very little of your physical matter remains from a decade ago. Despite this complete material turnover, you likely feel that you are numerically the same person you were as a child. This suggests that your identity might rely more on the continuity of your psychological pattern than on the persistence of specific atoms.

Most thinkers solve this riddle by prioritizing spatiotemporal continuity over material composition. As long as the change happens gradually rather than all at once, we generally accept that the object persists as a singular entity. You remain yourself because there is an unbroken chain of events linking your past self to your current form. If all your parts were swapped instantly, you might be viewed as a replica, but the gradual shift preserves your history. The Ship of Theseus teaches us that identity is often a concept we construct rather than a physical fact we observe.

Modern Pop Culture and Real-World Examples

You might have encountered this ancient riddle while watching the finale of Marvel’s WandaVision. When two versions of the android Vision confront each other, they use this exact thought experiment to resolve their conflict without violence. One version possesses the original body but lacks the data, while the other holds the memories but inhabits a magically recreated body. This scene perfectly illustrates the puzzle by asking if identity is tied to our physical components or the continuity of our experiences. It forces you to consider whether a being remains the same entity once the mind is separated from the original hardware.

You face this dilemma whenever you look at a heavily restored classic car or a renovated historical building. Collectors often debate whether a vintage vehicle remains authentic if the engine, chassis, and body panels have all been swapped out for new parts over the decades. If every rusty bolt is replaced during a restoration, you have to decide if the car is still the original antique or merely a shiny replica. This distinction matters deeply in legal and financial contexts because original artifacts command much higher prices than reproductions. The physical continuity of the object battles against its functional identity, leaving you to judge what truly defines the essence of the machine.

Consider what happens if a mechanic gathers all the discarded scrap parts to build a second vehicle. Thomas Hobbes expanded the original puzzle with this scenario, creating a situation where two different objects both have a valid claim to the same identity. You are left with one car that has the continuous history and another that contains the actual original matter of the prototype. This paradox challenges your intuition because it suggests that identity might not be a singular trait but rather a matter of perspective. These practical examples show that the Ship of Theseus is not just an abstract theory but a question of how you value continuity in the real world.

Rethinking Identity Beyond Material Substance

At its core, the Ship of Theseus compels you to question the stability of the physical world around you. By considering whether the vessel docked in Athens is the same one that left Crete, you realize that identity might be more about continuity than material substance. Thomas Hobbes’ addition of the reassembled planks deepens this mystery, compelling you to choose between historical significance and physical composition. This ancient thought experiment ensures you will never look at a restored classic car or even your own aging body quite the same way again.

The most profound implication of this paradox lies in how you view your own existence over time. Just like those replaced wooden planks, your biological cells regenerate and your memories evolve, yet you still feel like the same person you were a decade ago. This philosophical puzzle suggests that you are not merely a collection of atoms, but rather a persistent pattern or narrative surviving through constant flux. Embracing this fluidity allows you to accept change not as a loss of self, but as the very mechanism that keeps your identity alive.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core question of the Ship of Theseus paradox?

The paradox asks whether an object remains the same entity after all its original components have been replaced. You are challenged to decide if identity is defined by the physical material of an object or by its continuous history and form.

2. Where did the story of the Ship of Theseus originate?

This philosophical puzzle is attributed to the Greek historian Plutarch. He described how Athenians preserved the galley of Theseus by replacing rotting planks one by one, sparking a debate among thinkers about the nature of growth and persistence.

3. How does Thomas Hobbes complicate the original puzzle?

Hobbes introduced a twist where the discarded, rotting planks are reassembled into a second ship alongside the restored one. This forces you to confront a scenario with two distinct ships claiming to be the original, deepening the inquiry into what constitutes true identity.

4. How does the Ship of Theseus apply to human identity?

It serves as a metaphor for your own existence, questioning if you remain the same person as you age and your cells regenerate. You must consider whether your personal identity is tied to your physical body or to the continuity of your consciousness and memories.

5. What are the two main arguments regarding the ship’s identity?

One perspective argues that the ship remains the same because its form and function are preserved through continuous repair. The opposing view suggests that once the original material is gone, the object has fundamentally changed and lost its original identity.

6. Is there a definitive solution to the Ship of Theseus riddle?

There is no single agreed-upon answer, as the puzzle is designed to explore the boundaries of how we define existence. Your conclusion ultimately depends on whether you prioritize physical matter or abstract continuity when defining what makes an object unique.